The Origins of The Stoic Handbook (with Sketches)

Take a look at my original sketches that were the basis for what became The Stoic Handbook.

I have always been impressed with the amount of wisdom that can be condensed into a single sentence or paragraph by some of the great sages in history like Epictetus, Lao Tzu, and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.

— Friedrich Nietzsche

It's possible to read some of the great, short philosophical books in a day or two. You can read the Tao Te Ching and The Enchiridion in a couple hours.

While reading these books, you can gain an illusion of understanding, but more often than not the ideas you acquire are not durable and you don't integrate them into who you are.

Marcus Aurelius described life as follows:

The art of living is more like wrestling than dancing, in so far as it stands ready against the accidental and the unforeseen, and is not apt to fall.

I think Marcus was onto something here. I've been practicing Brazilian jiu-jitsu for quite a few years now, and I'm obsessed with the question of how one can learn optimally.

In Brazilian jiu-jitsu, you have access to thousands of video instructionals and the best teachers on earth. But in my experience, having access to all this knowledge doesn't help people learn more quickly and become better.

You can watch 15 hours of a video instructional, and in that 15 hours there might be 350 pieces of information, and out of those 350 pieces of information 150 of those pieces could be actual moves.

For every move there are 5-10 steps, and the success of performing each move against a skilled and resisting opponent relies heavily on remembering the details in a way that is automatic and precise, and using it with the exact right context.

Watching a 15 hour jiu-jitsu instructional from beginning to end, is very similar to just reading a Stoicism book. We can learn that it is possible, and link some new ideas to some existing pieces of knowledge we have, but the idea that we will call out the correct Stoic move under stress, in the right context, against a resisting opponent, and remember each detail in a precise yet automatic way is almost laughable.

The math here both frustrated me, but also excited me. Are there ways to learn more effectively? The answer is that there are, but the research shows that the methods are often counterintuitive.

I'm going to be explaining many approaches to effective learning over the coming posts, but today I want to tell you about the one that sparked the idea for The Stoic Handbook.

Recreating Mental Models

We learn by creating mental models. At first these models are very simplistic, but overtime as our knowledge builds and and intersects with existing ideas, the models become more and more complex. A world class baseball player, for example, has mental models for determining the type of pitch he will receive based on tiny micro-movements the pitcher exhibits before the ball leaves their hand.

To flesh out your mental models properly there needs to be adequate amounts of retrieval practice, but to start things off, one of the best things you can do is simply deconstruct and then reconstruct the information you want to learn.

For me this became a project of rewriting ancient wisdom texts and creating new models based on my understanding of them.

Below I'll show you some of my original drawings and diagrams from my sketch book, that eventually became the inspiration for the digital, online version of this website. I'll provide a link to my breakdown of each chapter in the heading.

These personal drawings have never been published before.

Use this as inspiration to create your own deconstruction of ancient wisdom. You can breakdown my posts each week too. This is what my friend Conrad does. Whenever he receives an email from me, he doesn't just read it, but he "grapples" with the ideas in a notebook.

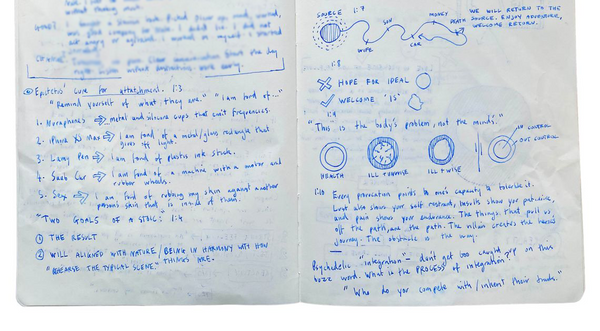

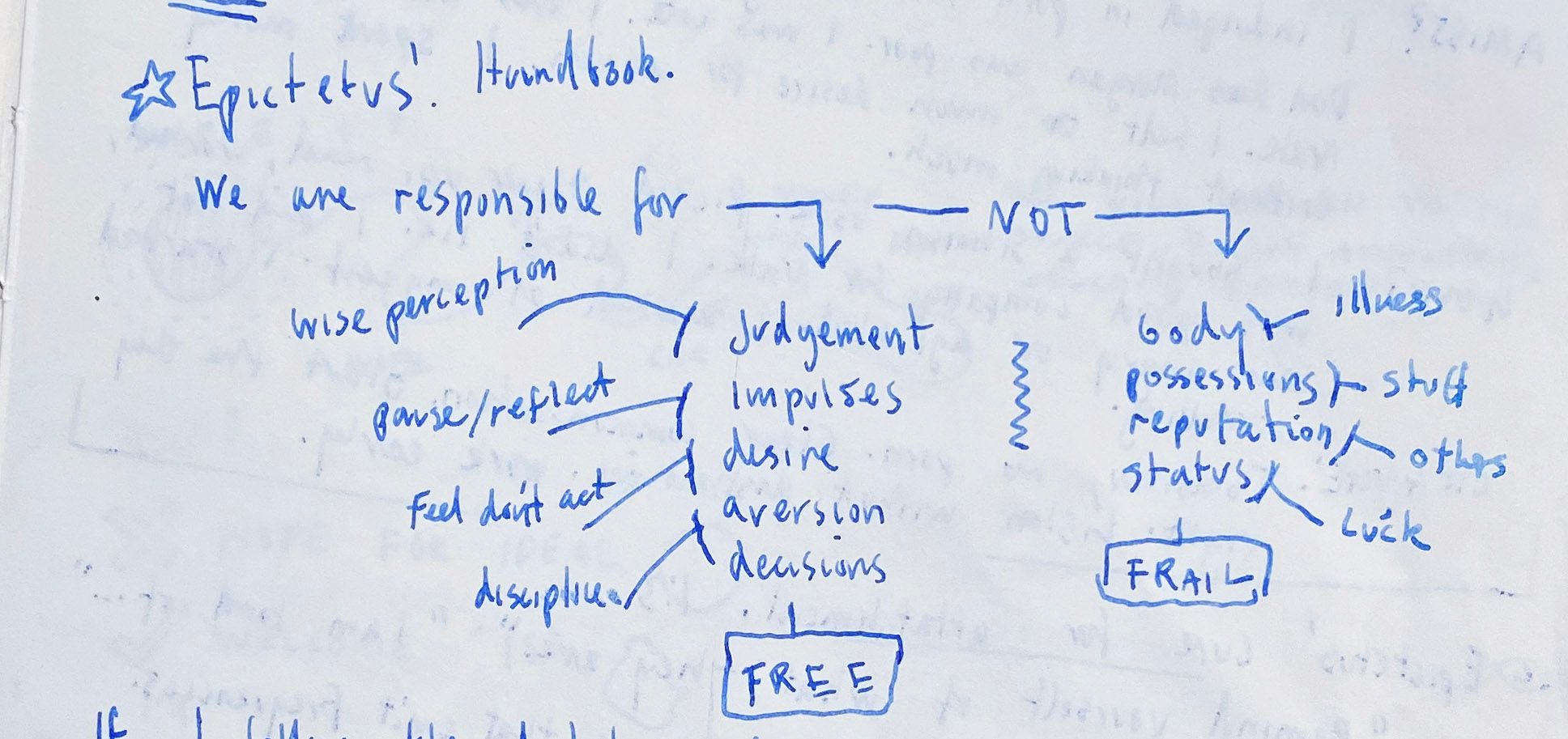

Chapter 1: The Dichotomy of Control

We are responsible for some things, while there are others for which we cannot be held responsible. The former include our judgement, our impulse, our desire, aversion and our mental faculties in general; the latter include the body, material possessions, our reputation, status – in a word, anything not in our power to control.

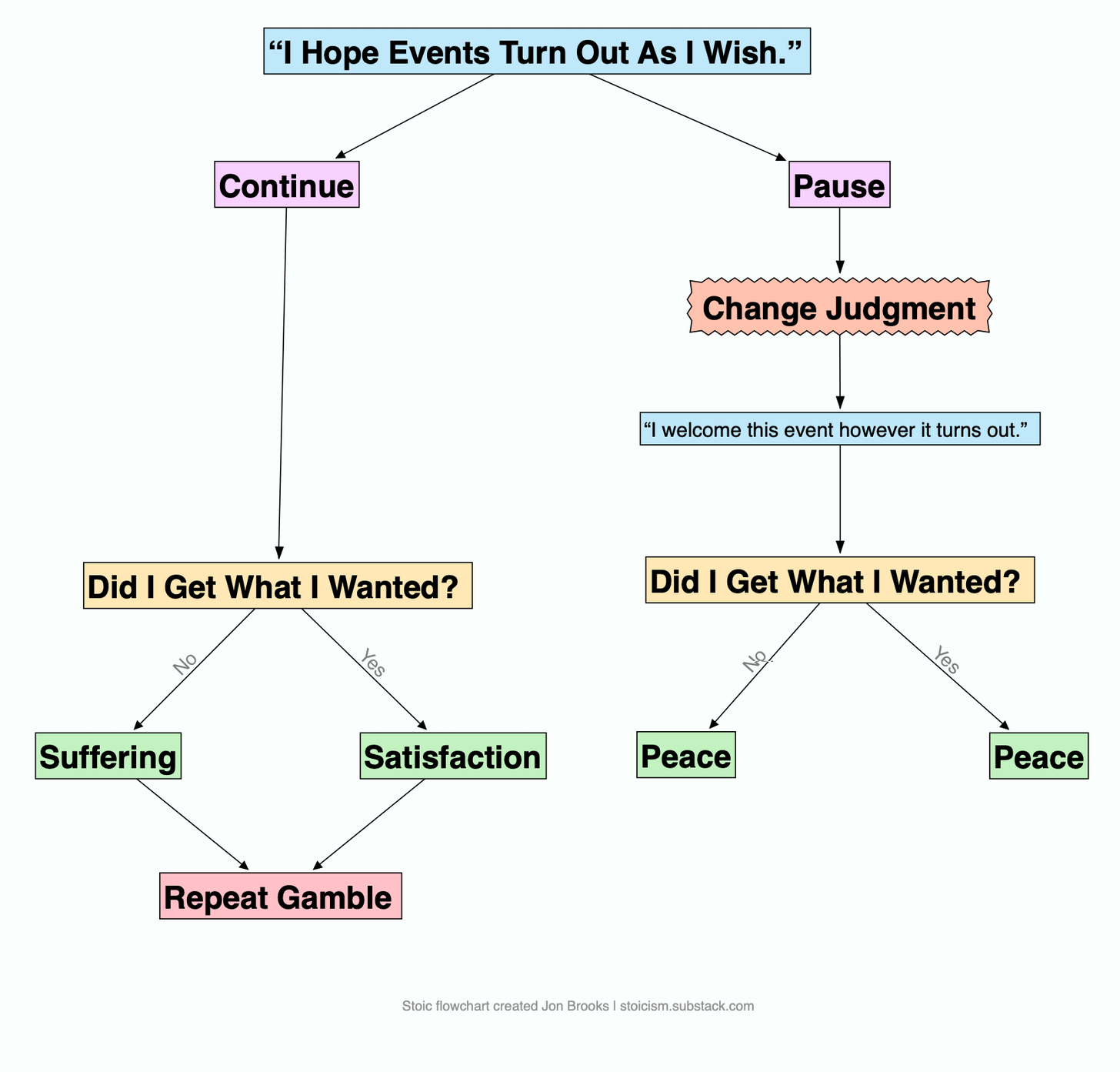

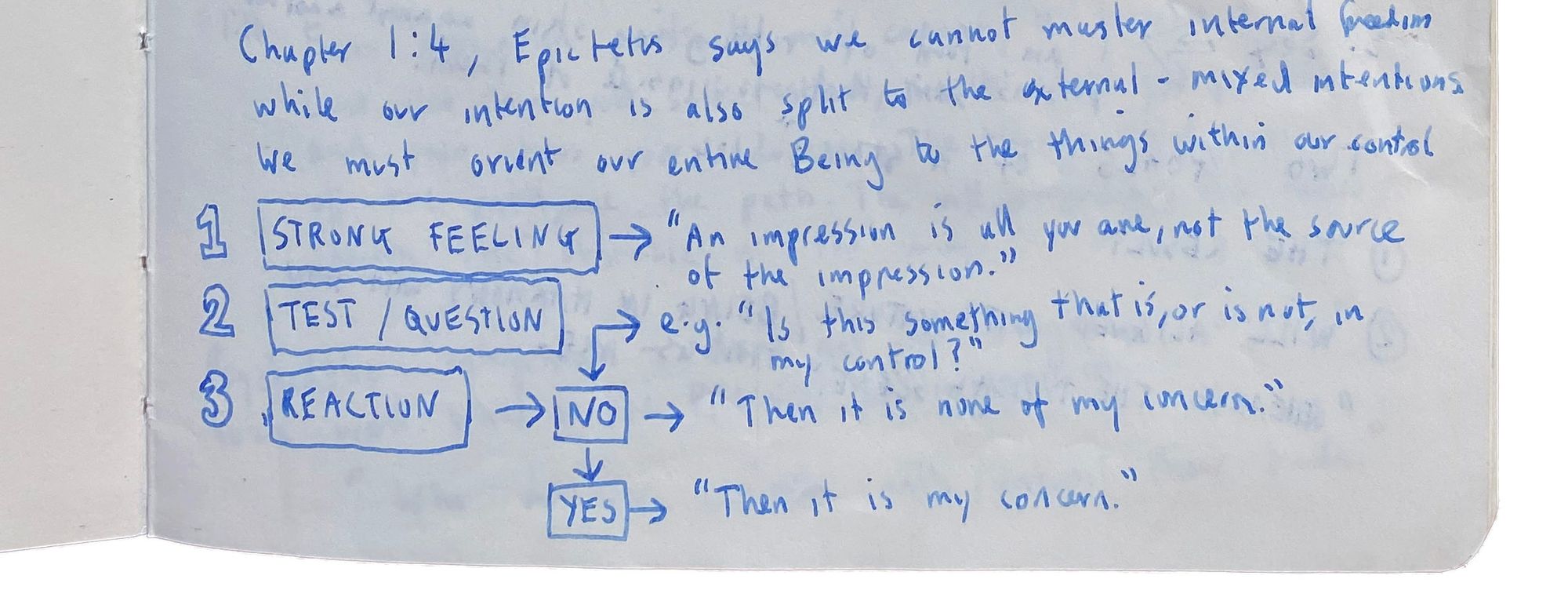

So make a practice at once of saying to every strong impression: ‘An impression is all you are, not the source of the impression.’ Then test and assess it with your criteria, but one primarily: ask, ‘Is this something that is, or is not, in my control?’ And if it’s not one of the things that you control, be ready with the reaction, ‘Then it’s none of my concern.’

Chapter 7: Nothing Is Lost, Only Returned

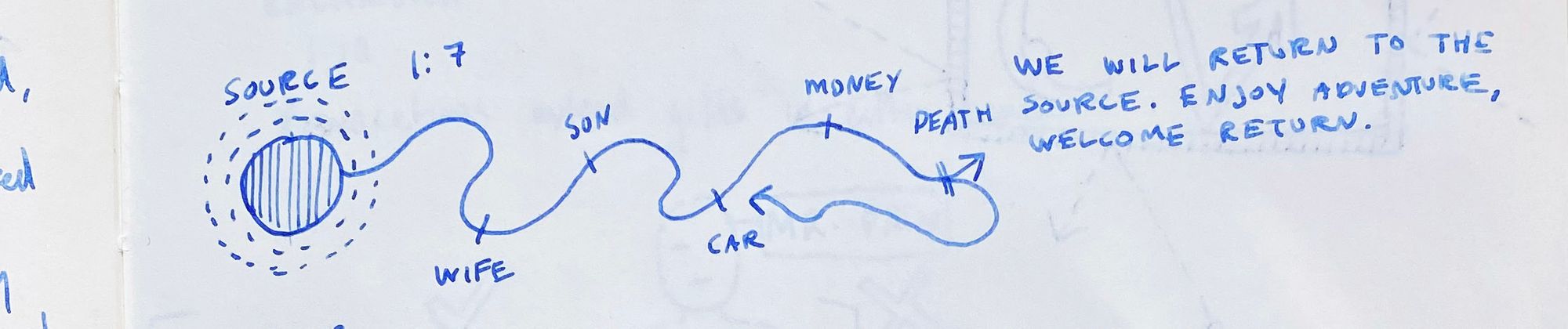

If you are a sailor on board a ship that makes port, you may decide to go ashore to bring back water. Along the way you may stop to collect shellfish, or pick greens. But you always have to remember the ship and listen for the captain’s signal to return. When he calls, you have to drop everything, otherwise you could be bound and thrown on board like the livestock.

Chapter 9: Illness is Only a Problem for the Body

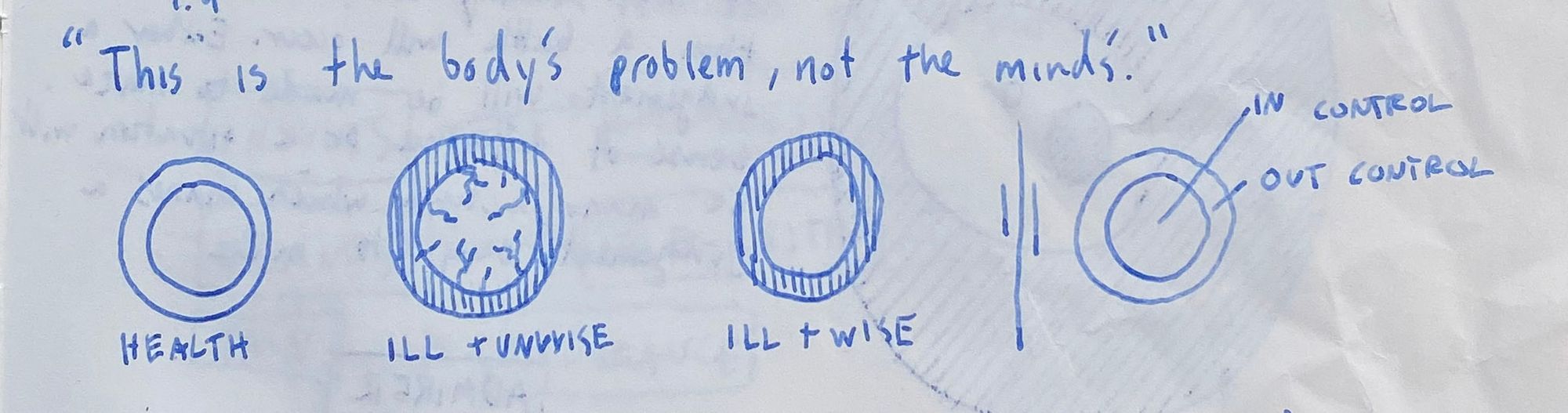

Sickness is a problem for the body, not the mind – unless the mind decides that it is a problem. Lameness, too, is the body’s problem, not the mind’s. Say this to yourself whatever the circumstance and you will find without fail that the problem pertains to something else, not to you.

Chapter 10: Every Challenge is a Gift

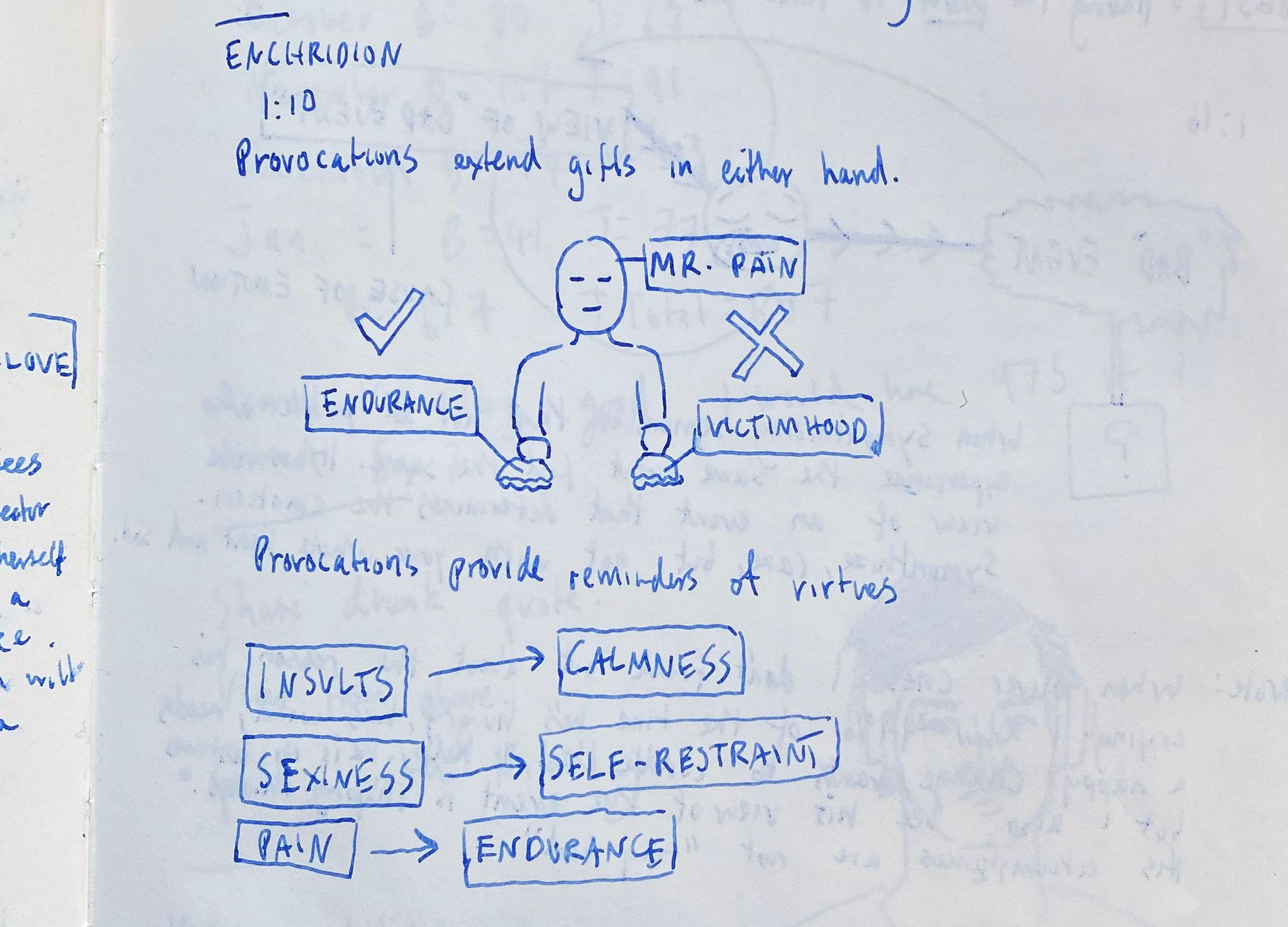

For every challenge, remember the resources you have within you to cope with it. Provoked by the sight of a handsome man or a beautiful woman, you will discover within you the contrary power of self-restraint. Faced with pain, you will discover the power of endurance. If you are insulted, you will discover patience. In time, you will grow to be confident that there is not a single impression that you will not have the moral means to tolerate.

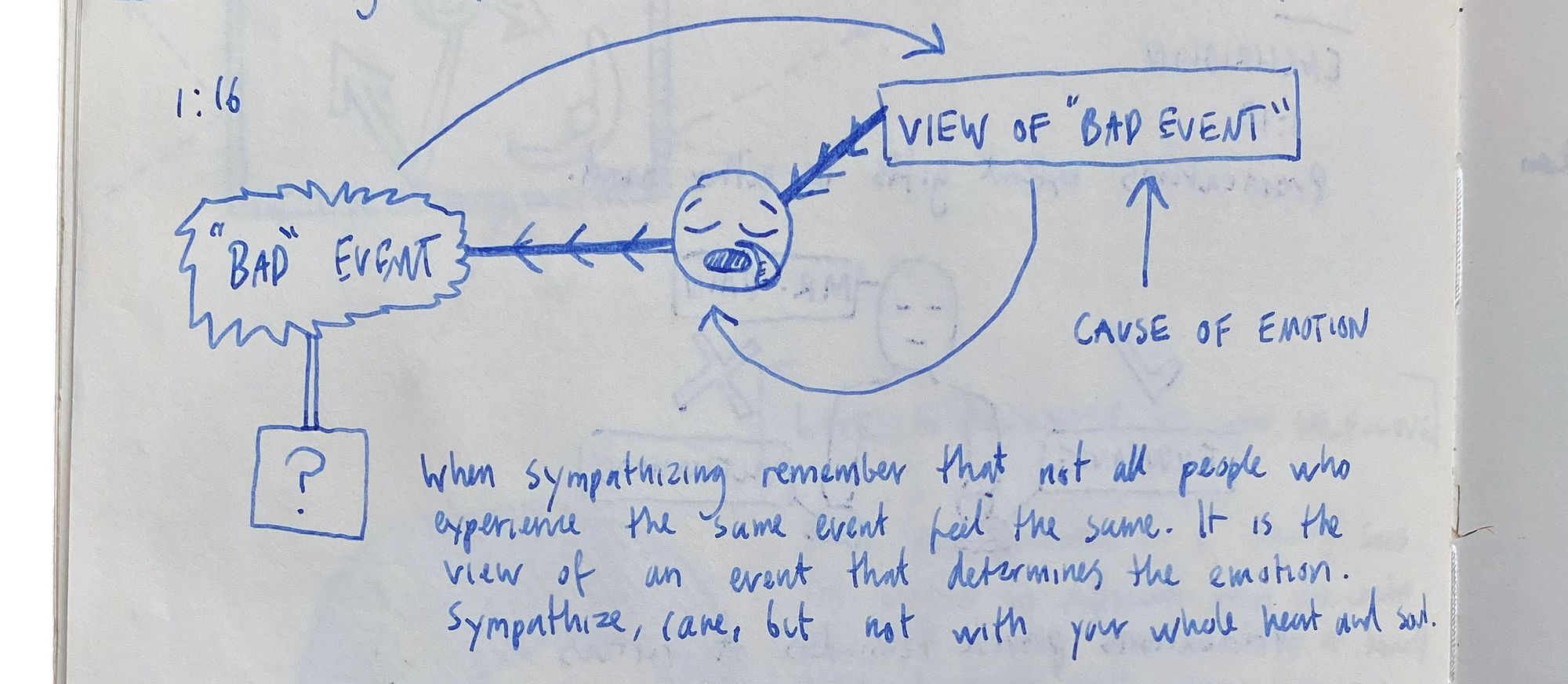

Chapter 16: How Stoics Sympathise with Others

Whenever you see someone in tears, distraught because they are parted from a child, or have met with some material loss, be careful lest the impression move you to believe that their circumstances are truly bad. Have ready the reflection that they are not upset by what happened – because other people are not upset when the same thing happens to them – but by their own view of the matter.

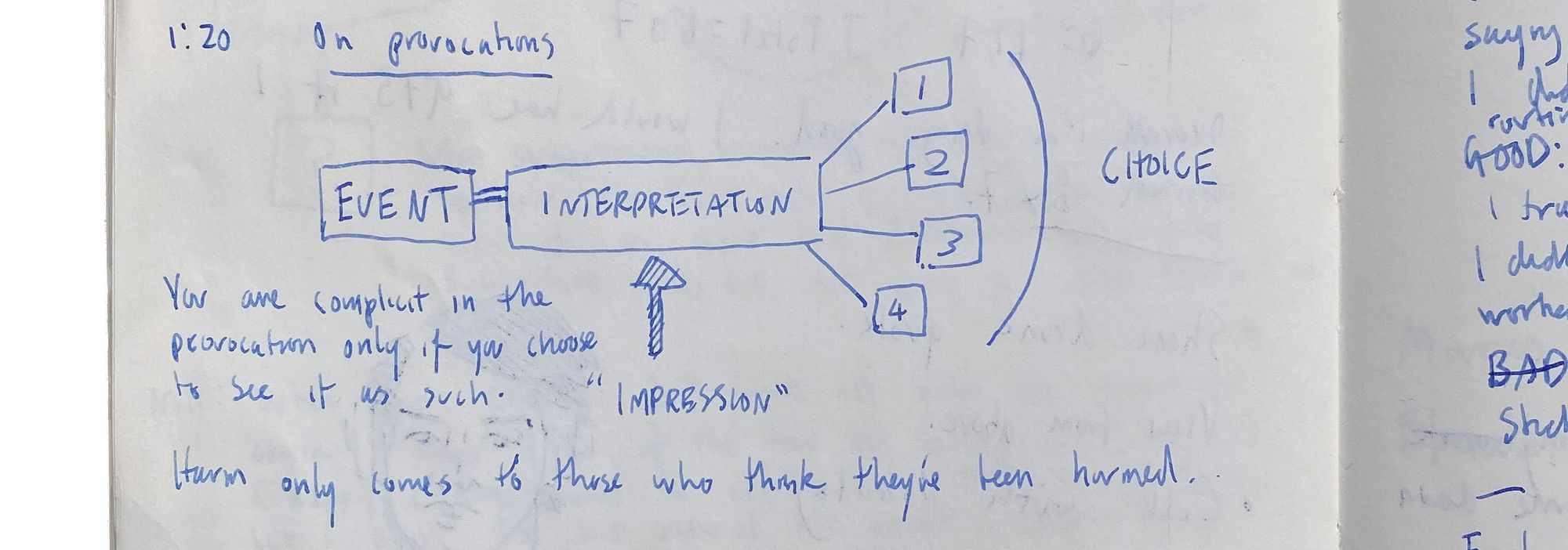

Chapter 20: Being Provoked is a Choice

Remember, it is not enough to be hit or insulted to be harmed, you must believe that you are being harmed. If someone succeeds in provoking you, realize that your mind is complicit in the provocation.

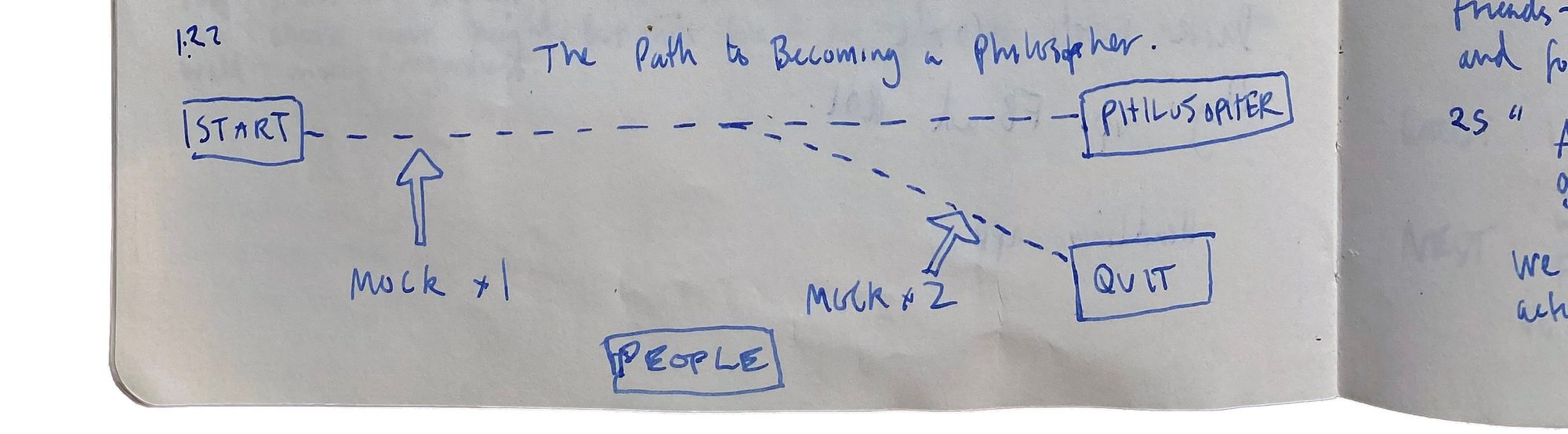

Chapter 22: The Path of the Philosopher

If you commit to philosophy, be prepared at once to be laughed at and made the butt of many snide remarks, like, ‘Suddenly there’s a philosopher among us!’ and ‘What makes him so pretentious now?’ Only don’t be pretentious: just stick to your principles as if God had made you accept the role of philosopher. And rest assured that, if you remain true to them, the same people who made fun of you will come to admire you in time; whereas, if you let these people dissuade you from your choice, you will earn their derision twice over.